“Goodbye to the future. The last days of Tokyo’s Nakagin capsule tower”.

I saw this article a while ago. It is fascinating to see the past visions of the future now being torn down because they wore out long before any vision of them came true.

The most interesting part was the response this news was getting. The top comment was as follows:

“Travelling to the 70s must feel like going to the future: these futuristic capsule buildings existed, supersonic air travel was commonplace, and there were humans travelling to the moon. The epitome of modernity these days is how fast your car videos can load.”

The Nakagin tower, built in 1972, is a classic example of the mythic pseudofuture — people in the present building something that they thought represented the future. I’m impressed that people are thinking along the lines of that first comment; from there, it’s not far to the realization that industrial civilization peaked in the 1970s and it’s all been downhill from there.

Which brings me to the point of this essay. Rumours of the impending collapse of our high-technological industrial civilization are – to put it mildly, quite late. Like getting a notification from your airline that your flight will be delayed – two months after you missed it.

I have mentioned in previous posts that this newsletter assumes you are either aware of, or bought into, the reality of catabolic collapse. I’m not interested in debating whether it is a real process (as anyone with eyes and ears and common sense can tell that it is), I’m much more open to discussion on what is to be done and how we should then live. I have not written a post explaining how or why I came to this position.

This is that post.

It was the spring of 2014 when I had just walked into a classroom in Faner Hall; I was early for a philosophy lecture so while waiting my attention was drawn to a small stack of zines. Ordinarily I would have dismissed this stuff but a few words of copy on the front page struck me as unusual – NOMOS OF THE EARTH – and I read the whole thing while waiting for class to begin.

Reader, it was not long before I went all the way down the rabbit hole.

I started by looking up the author John Michael Greer’s entire body of work on the Archdruid Report and read through almost the whole of it in less than two months, and the pieces of the puzzle started falling into place.

There was, to begin with, Hagbard’s Law, the failure of most elite professions, including medicine, to police themselves, and the corruption of institutional science by the monied interests who supply grant money in the tacit expectation that whatever research ends up getting published will reflect favorably on their products. I learned about concepts like Jevons Paradox, the Hubbert Curve and its ramifications for our energy future1. Before long I started reading Vaclav Smil, Gail Tverberg, and others in the energy/resource sphere.

And so I saw it clearly now for the first time the underlying structure of the Modern World: the Myth of Progress.

The confidence that every problem must have a technological solution.

The ahistorical blindness that lead us to think the Present is always and everywhere better than the Past, and our ancestors were benighted ignorant bigots not worth studying because we Moderns simply know better.

The desire of psychiatrists to conquer their little piece of nature by chemically suppressing emotions and behaviors that they found undesirable.

The fear among parents that one’s child will start off on the wrong foot in life if he doesn’t benefit from the latest technology, pedagogical and medical interventions.

The overweening certainty that human innovation could invent a better tree than nature, or a “cruelty-free egg”, or grow meat in a lab (when you eat lab-grown meat, you’re eating tumors, by the way); and that somehow we SHOULD, just because we CAN.

The confidence that because a certain technology definitely works (i.e. putting a child on Ritalin really does help him focus) it can’t have any downsides that are worth worrying about.

The belief, on the part of up and coming pharmacologists, that because the past greats in their field had improved the human condition by discovering drugs that could treat previously untreatable conditions like syphilis, the process must be repeatable indefinitely without running into diminishing or negative returns2.

And once I saw the Myth of Progress for what it was – an irrational delusion that had led to untold millions of people being mentally destroyed by people who often didn’t mean them any harm – then I could see the same dynamic elsewhere.

I soon became convinced that the collapseniks were right about a great many other things – how industrial civilization was fragile and self-limiting, how our culture’s clueless treatment of the environment that keeps us all alive was doing us in, how there really is no good reason to believe that whatever energy sources the world is using in 2100 will have all the benefits of the current ones without their drawbacks, and so forth.

Have you ever asked yourself why the promises and vision of a post-scarcity future started and ended in the 20th century?

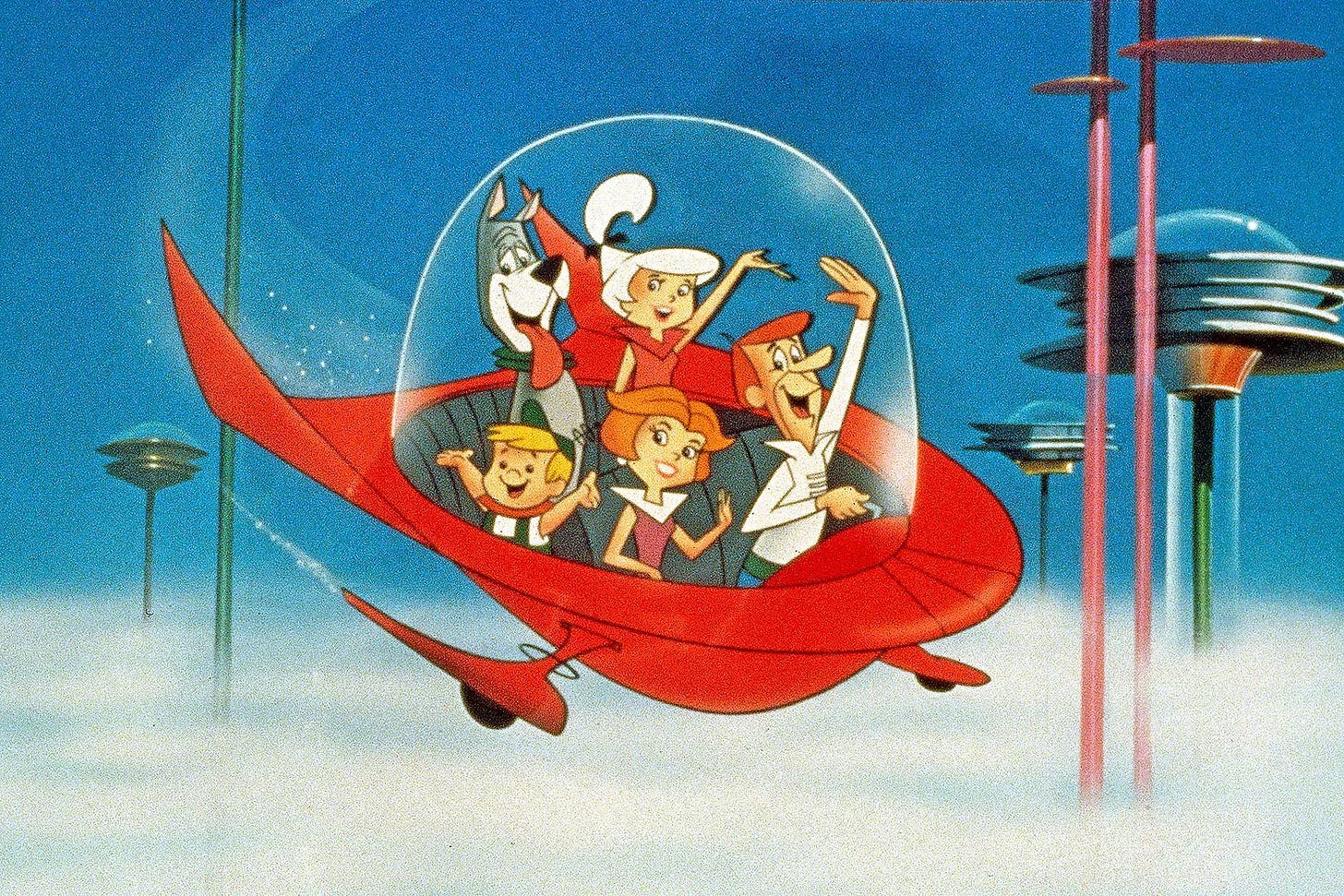

Many of the younger generation won’t remember this but the high water mark of humanity’s techno-optimism truly is exemplified by the Jetsons. People living in the clouds, cars powered by miniature fusion reactors, robot maids with sophisticated AI and lifelike personalities, effortless space travel. This was around the same time as the original run of Star Trek, and of course, 2001: A Space Odyssey.

The TYPE of future scenario we get in pop culture is downstream of a society’s general zeitgeist or optimism in the future. In the 50s and 60s it seemed as though there was no limit to what our scientific prowess could do. We had mastered the atom – next stop, the stars!

And now? Dystopia.

Most hypothetical scenarios of the future look like some variant of Mad Max, The Hunger Games, or Snowpiercer. Some of you more canny readers will will point out that books/shows like Altered Carbon take place in a universe where FTL travel is possible. Except it’s not.

The “sleeve” technology employed in that universe exists precisely because humanity had not yet cracked the code of interplanetary travel that happens within human lifespans. Hence, faxing human souls between worlds was the next best thing.

Modern science is exhausted. We haven’t innovated a new form of battery, let alone propulsion, in over 50 years. NASA boasted a second mission to the moon by 2015 and a permanent lunar base by 2020. Let’s, er, see how that’s going.

Even simply continuing on our current course of growth – or simply sustaining our lifestyles of presumed industrial abundance – would require unfathomable leaps in technology.

To separate two of the examples in this post, even for those who aren’t really expecting a Jetsons lifestyle, there’s a powerful belief that something like fusion energy will come along (because surely “they” will think of something) to keep everything humming at least at its current level. Folks, people smarter than you and me have been throwing their best into cracking the problem of fusion and thorium reactors for decades to no avail.

An increasing Red Queen effect (combined with, as you’ve noted, the dawning realization among the Zoom classes that the lifestyle all this has allowed so far kind of…sucked) will provide more interesting times to come.

In case you were wondering, there is really not much you or I can “do”. The best chance humanity had to divert themselves from this path of ultrahigh energy consumption was the 1970s. The second best time was the late 2000s. Path dependency is a blind idiot goddess and she will not be denied.

At this point I have no substantive thoughts, only notes on several fixed ideas in Modern culture:

The only acceptable response to any problem is to throw lots of money at it in the expectation of developing some increasingly complex and expensive technology as the only possible solution. i.e., we recycle (some stuff… if, and only if, the technology is available) but are never encouraged to reduce or – God forbid! – reuse.

Places that have not modernized are “charming vacation destinations” and suburbanites flock there for temporary escapes from their daily existence, but wouldn’t for a moment consider actually living there, because they are horrified at the idea of doing “menial” jobs that people who actually live there have to do.

Both the techno-utopia and the eco-utopias are always written about in the most romantic and glowing terms — by people who have never experienced either.

Awkward logistical questions, such as how to supply and power either the techno-utopia or the eco-utopia, are papered over or just plain ignored.

Style is curiously bland and mind numbingly boring in the futuristic worlds of the technophiles. (Why is that? Why is it the worlds of Star Trek or Star Wars are so devoid of style, whereas depictions of Hogwarts or the Elven kingdoms of LOTR always exhibit so much and grace and elegance?)

To save face, discount any failure as trivial and claim that wasn’t the objective anyway. (To be fair, this may actually be a general human trait, but it is very definitely characteristic of this society at this time.)

So to sum it all up, that is how I became deconverted from the Cult of Progress: I saw its effects in my own life, and the lives of people I cared about, and I became convinced that what was going on could only be explained by the same irrational faith in Progress which drives all the other delusions which are dissected in painstaking detail on this corner of the Internet.

Closing thoughts

Whatever concentrated carbon we have used is diffused into the biosphere. You cannot, having drank the milk, put it back in the bottle.

The real boom in oil production began immediately before WWII. We can call “Peak Oil” somewhere around 2010 and be reasonably accurate (that is accurate enough – drilling down further only makes for massive controversy). While the initial oil rush was around the turn of the century, it took the IC engine to really boost it. So let’s say for conversations sake that the uphill slope of the “petroleum curve” was a hundred years back, and the actual peak was a decade ago.

Our current reality runs on oil – from electrical power to wire insulation to plastic bags to polyester fibers, etc.

Most of the things we utilize today, taken for granted by 99.999% of living humans, were just not around in 1920. As example – electrical wiring was insulated with cloth fiber wrapping, not plastic coating.

The current crop of petroleum based ‘stuff’ isn’t going away any time soon. From cradle to grave the average human interacts with objects that are either derived from petroleum in the form of plastics e.g., polyester clothing, plastic clingwrap, melamine plates, disposable and reusable water bottles and food containers, etc.

We turned petroleum into calories and used that to feed 7 billion people. In a very long circuitous way you can even say the Green Revolution was a magic trick whereby we converted petroleum INTO people.

What happens next? Well, short of some fantastic discoveries in energy resources, we will experience a long and drawn out slide down the tech curve until we hit a new energy equilibrium. The things developed and built using oil products are quite likely going to be with the next generation, or three, or even five – but they will become very expensive. That will lead us, perhaps, back to fiber wrapped wiring insulation from a century back, or else some other new ideas sans petroleum.

What I visualize happening is not Mad Max, but a dialling back of using plastic to reduce cost (unless microbes can make it, but then we are onto the genetic nightmare trail, so let’s hope not).

Not a return to pre-industrial levels of technology overall, but a rightsizing. Similar to what the Amish and Mennonites currently practice. Appropriate technology, fit for purpose, only what the community actually understand, and only that which maximises utility and minimises harm3.

Appropriate tech, not low tech.

A reduction in excess traveling has already been handed to us by the non-Pandemic, but it will be really evident when ships begin using wind again, even as an adjunct to oil.

There is no reason we cannot return to glass bottles, paper sacks and many other things that are both renewable and reusable.

There is no reason ships cannot take a week longer to cross an ocean.

This is not the future many people wants, and it sucks because we have been collectively brainwashed into thinking that our species is destined for the stars. Man’s manifest destiny writ large across the galaxy.

I find the Star Trek future extremely unlikely. Observation tells me that things will become slower paced rather than high-energy.

Life itself will be more localised, not hyper-global.

There are worse things that can happen.

If you understand the principle by which Hubbert’s curve works, it is not a difficult maneuver to see how it applies to basically every other resource on this planet.

You might not want to look up the rise in antibiotic-resistant bacteria, such knowledge is not for the faint of heart.

In no future scenario do I believe there is a place for smartphones. Simply not enough utility to justify the horrific investment of energy, resources, and manpower. Sorry people, I think that African kids should be allowed to live an idyllic life frolicking around and collecting nuts from mongongo trees instead of dying in the cobalt mines.

Hell yes, I'm always glad to see Greer get mentioned on Substack.

I stumbled onto him in 2012, and what he was saying immediately clicked with me, and gave me context for the insanity I was seeing in Phoenix..

Good to see more Greer-pilled writers around here.